These men and women are inspiring examples of grit, drive and imagination. Their success attests to the enduring impact of our rich Kingman County heritage and reminds all of us...

You can get ANYWHERE from Kingman.

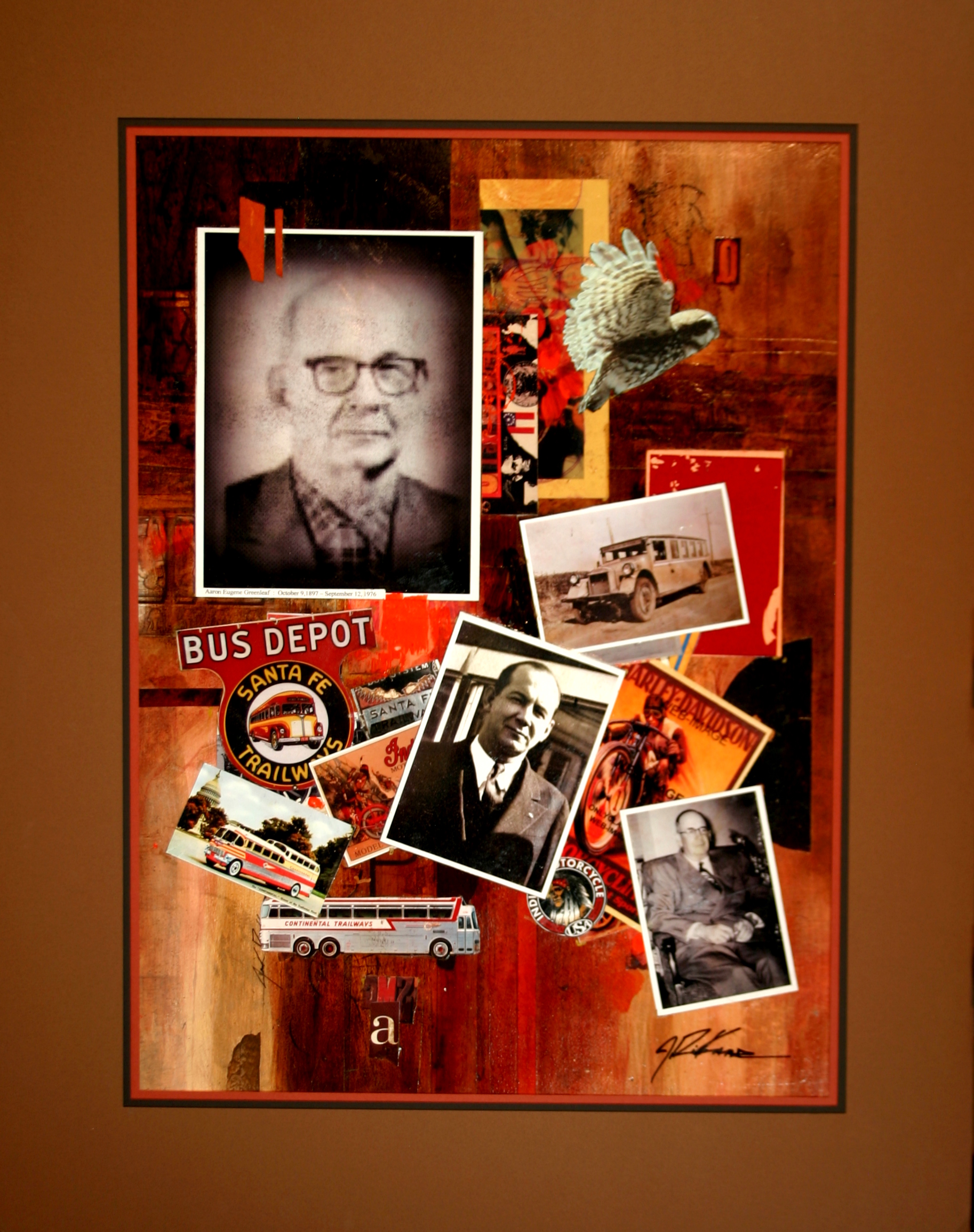

1897-1976

“If you want to get somewhere, help other people get to where they want to go” may have been the thought that drove a Kingman County farm boy to build a fortune and a transportation system that stretched across America. It all started back when most school kids were riding horses and buggies. But not Aaron Greenleaf. He was whizzing along country roads, over wheat fields and around downtown Kingman on a motorcycle. He kicked up lots of dust and lots of tempers. Aaron loved speed and adventure. He rode over many prairie miles to participate in and spark challenge races in several counties. At 13, he even rode his two-wheeler from Kingman to Colorado and to the top of Pike’s Peak. It was 1910, the summer before he entered Kingman High School. Two years later the spirited teenager was enrolled at the Staunton Virginia Military Academy. Perhaps his parents thought military discipline would temper his adventurous spirit. It didn’t work. After a short while, he ran away from the military school, joined the Army and was soon headed to Europe and World War I. Aaron landed his dream assignment. He became a motorcycle dispatch rider and carried messages to frontline combat units in France. It was one of the most daring jobs in the war. German riflemen zeroed in on motorcycle couriers. After the Armistice, Private Greenleaf was selected to join the elite honor guard for General “Black Jack” Pershing at AEF headquarters in Paris. Returning to Kingman in 1919, his routine became a forage to make living expenses. Amid a grind of odd jobs, Aaron found a way to travel for pay. He borrowed his father’s small sedan and began hauling traveling salesmen between Kingman and Wichita. Soon, he was able to finance the purchase of a Lexington, a seven passenger touring car. With it, he launched Kingman’s first taxi service and started a daily passenger run to Wichita, leaving from the Overland Hotel. Business was spotty. Flat tires, breakdowns and railroads were tough competition. However, when Aaron promised to beat the train from Wichita by two hours, he secured a contract to deliver the Wichita Beacon to Kingman. He began to prosper, and the steady newspaper haul enabled him to extend a passenger and newspaper route to Pratt. The business was named Greenleaf Stage Lines. To take care of expanding business, he created a larger car. By cutting two cars apart and then welding them into one, he doubled passenger and luggage space. He added cars and drivers, and in 1924 took on a partner, D.E. Sauder, a former railroad brakeman. More expansion followed. Aaron designed the first 17-passenger vehicle in Kansas, maybe the first in the nation. Soon they were serving passengers in dozens of towns and three states. The firm’s name was changed to Southern Kansas Stage Lines. Its main office was moved from Kingman to Wichita. Then approval was gained to expand passenger service to San Francisco. They also entered into co-operative agreements with bus lines in the east and began the first transcontinental hookup between the two coasts. Within five years they had 50 buses serving 150 locations. Many of the 10,000 miles the Greenleaf buses traveled were still gravel roads. Expansion was almost continuous. Between acquisition of smaller lines and building their own depots, they launched a trucking business. It grew to encompass depots in 96 cities and 100 employees. Aaron is credited with the development of air conditioning in buses. This came in 1933 after they formed Santa Fe Trailways. Five years later, they sold to Santa Fe Railroad for millions. It was only 19 years after he hauled his first passenger from Kingman to Wichita.“